Guide to Observing with the VLA Complete Manual

Disposition Letter and Scheduling Blocks

Interpreting the Disposition Letter

A disposition letter is sent to the principal investigator and co-investigators of each VLA proposal. This letter contains comments from the cognizant Science Review Panel (SRP), a linear-rank score from the SRP, comments from the NRAO Technical Reviewer and, optionally, comments from the Time Allocation Committee (TAC). Guided by the linear-rank score and taking into account the time available, the TAC assigns a scheduling priority to each session in the proposal. If time is allocated at a scheduling priority of A, B, C or D, the proposal is converted to a project which is eligible to compete for time in the dynamic queue.

The VLA disposition letter is arranged in six portions:

Synopsis This portion lists the proposal id, title, type, authors, cognizant Science Review Panel (SRP), and time allocation summary. The latter tells the proposers whether or not time was allocated to the proposal. If time was allocated, its scheduling priority (A, B, C or D) is given and the proposers are responsible for preparing scheduling blocks for that time.

Comments from the TAC The TAC consists of the chairs of the eight SRPs. Taking into account the time available as a function of LST, the TAC assigns a scheduling priority to each session in each proposal. The TAC might comment on these assignments. The assigned scheduling priority depends on the linear-rank score of the proposal, the LST ranges involved in the session (daytime is harder to accommodate than nighttime), the total time requested in the session, and the competition from better-ranked proposals requesting time at similar LST ranges. For further details, refer to the VLA Prioritizer Memo.

Time Allocation For each session in the proposal, a table lists the session's name, array configuration, time in hours, LST range, bands and scheduling priority. For a given array configuration, time approved at a scheduling priority of A, B, C or D may be divided into multiple scheduling blocks as appropriate. Factors to consider in this division include the scheduling priorities, the observing frequencies, the tabulated LST ranges for the sessions, and the LST pressure plot at the start of the array configuration.

Further information for proposers and observers, including statistics and important LST pressure plots, is available from the most recent TAC report that is referenced in the disposition letter.

The possible scheduling priorities are:

- A = the observations will almost certainly be scheduled

- B = the observations will be scheduled on a best effort basis

- C = the observations will be scheduled as filler

- D = the observations will be scheduled as filler at the lowest priority

- N*= the observations will not be scheduled because they were explicitly rejected by the TAC

- N = the observations will not be scheduled because they could not fit in the time available

Unless otherwise stated in the TAC comments, Regular proposals with: priority B, C and D are eligible for scheduling only in the associated configuration or semester; priority A are automatically carried over for one additional configuration cycle or semester.

Shared Risk Observing (SRO) proposals will not be carried over if they cannot be scheduled for reasons associated with the shared risk component(s) of the observations, even if awarded priority A. Resident Shared Risk Observing (RSRO) proposals are not normally awarded priority A, but would be subject to the same conditions on carry-over as SRO proposals. (See also Re-Observation of FAILED Scheduling Blocks below).

Comments from the SRP This portion gives the linear-rank score from the SRP, along with comments from the SRP that summarize the proposal, give its strengths and weaknesses and, optionally, note any technical issues. The community-based SRP consists of a chair and five anonymous members. The linear-rank score is on a scale from 0 (a high-ranked proposal) to 10 (a low-ranked proposal).

Comments from the NRAO

This section contains instructions for submitting schedule files (see Schedule Creation and Submission below), information about the NRAO Student Observing Support program, and associated deadlines.

Further information for proposers and observers, including statistics and important GST pressure plots, is available from the most recent TAC report that is referenced in the disposition letter.

Comments from the NRAO Technical Reviewer Comments concerning the Technical Justification portion of the proposal, if a technical review has been performed. These comments are available to the SRP and the TAC.

Proceeding with Conversion of Proposal to Project

OVERVIEW

This section discusses converting your proposal to a project, checking the LST pressure plots and how to find the most current version (generated every Friday), scheduling block duration for the different priorities, and some tips on building your scheduling blocks.

Converting a Proposal to a Project

If a proposal's disposition letter indicates that time is allocated at a scheduling priority of A, B, C or D, then NRAO staff will convert the proposal to a project in the Observation Preparation Tool (OPT). This conversion occurs only about a month before the start of an array configuration (see the latest configuration schedule).

After the conversion is complete, the project's authors are notified that the project is ready in the OPT. A project contains one or more program blocks. A given program block will involve only one array configuration (which may be Any) and only one scheduling priority. The project's authors are responsible for atomizing a program block into scheduling blocks.

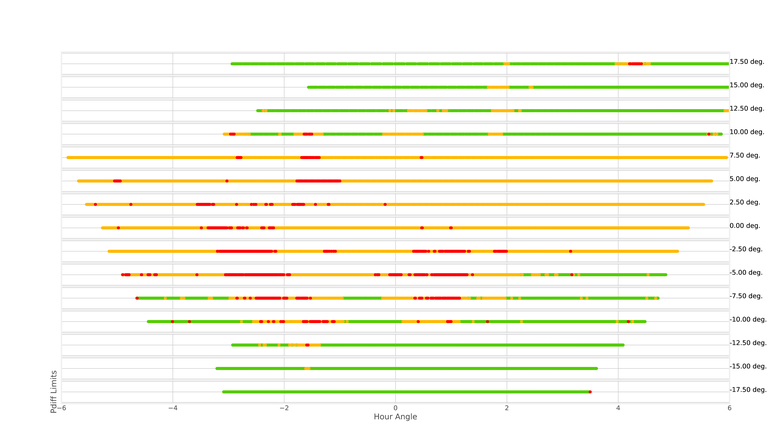

Interpreting the LST Pressure Plot

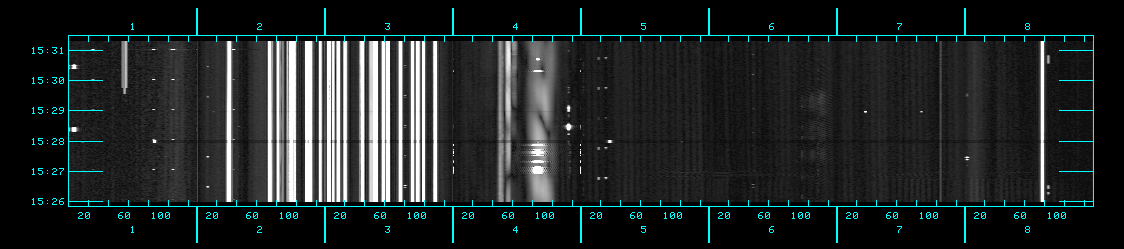

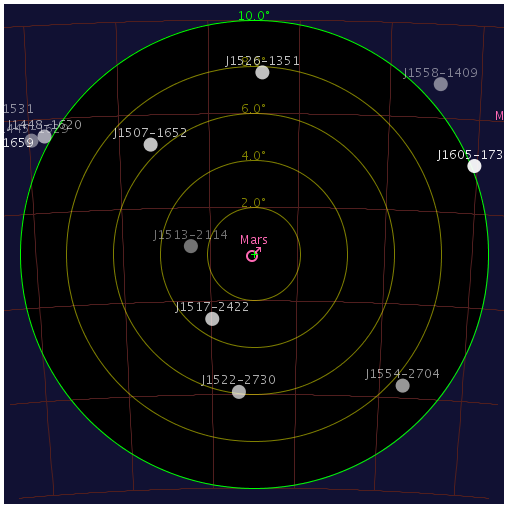

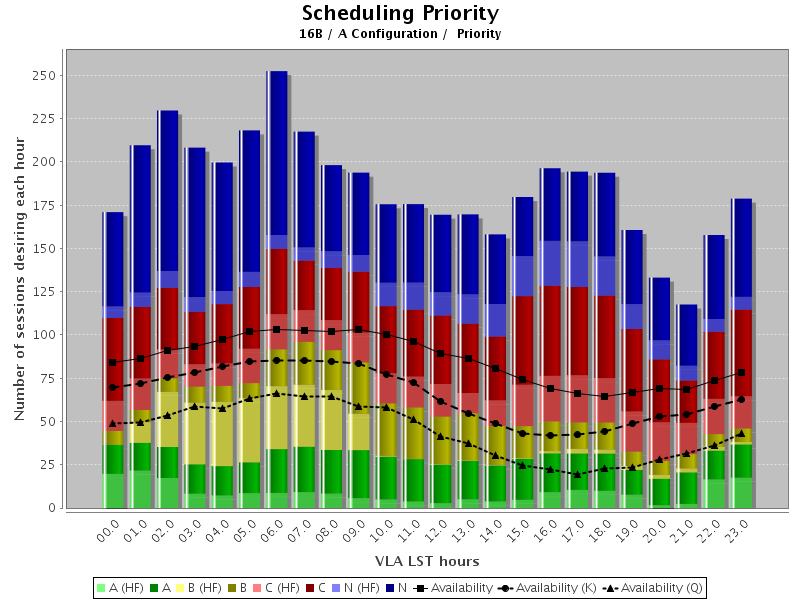

Figure 1.1 (below) shows an example of the pressure on dynamic time as a function of LST for the start of an array configuration; this example is for the A-configuration in Semester 2016B. Similar pressure plots are available for each configuration in each semester and are published in the Time Allocation Committee (TAC) report for the semester.

Figure 1.1 encodes pressure by the scheduling priority assigned by the TAC, as well as by frequencies above 12 GHz (light shading) and below 12 GHz (dark shading). The time available per LST hour is shown by the solid black line for all frequencies, by the long-dashed black line for K-band conditions, and by the short-dashed black line for Q-band conditions. Maintenance, software and enhancement activities cause the thick black line to be less than the total number of LST days in the configuration. Such activities dominantly occur during daytime, causing the black lines to dip for the daytime LST range.

Scheduling priorities assigned by the TAC are encoded by color, with the following meaning:

- A = the observations will almost certainly be scheduled (light green, dark green)

- B = the observations will be scheduled on a best effort basis (light yellow, dark yellow)

- C & D = the observations will be scheduled as filler (light red, dark red)

- N*, N = the observations will not be scheduled (light blue, dark blue)

A project allocated time at a scheduling priority of A, B, C or D is eligible to compete for time in the dynamic queue. To effectively schedule the VLA, it is necessary to approve more time than is actually available.

Scheduling Block Durations

The duration of an individual scheduling block (SB) cannot exceed the time allocated to its containing program block. Beyond that basic fact, the optimal duration of an SB depends strongly on the scheduling priority (A, B, C or D) assigned to its containing program block. As an aid for observers, a pressure plot for the dynamic queue is updated and posted every Friday, and is accessible from the Schedsoc Home Page.

Priority A: Dynamic scheduling enables priority A SBs to observe during the requested observing conditions, as determined at the start of the observation. SBs of any duration are fine as far as the heuristics in the dynamic scheduler are concerned. However, there may be other considerations in determining the best SB duration. At high frequencies the length of time during which the specified observing conditions, evaluated at the start of the run, can be expected to be satisfied during the duration of the run needs to be considered. This is a function of the time of day and time of year. Daytime observing is also be limited by maintenance, software or enhancement activities, so SBs that can end by 8am or start after 5pm (local Mountain time) have an advantage.

Priority B: The amount of priority B time approved is designed to almost fit into the available hours per configuration. However, it is advantageous to submit SBs of several different durations. SBs with durations of 4 hours, for example, are more efficient, but shorter SBs will often be scheduled earlier, as they can fit around the priority A SBs which are emphasized early in the configuration. Moreover, as noted above, shorter SBs are recommended at high frequencies.

Priority C & D: These are filler projects. Monitor Friday's pressure plot located near the top of the Schedsoc Home Page. Early in the configuration, only SBs with durations of 1 hour or less have any chance of being scheduled. Later in the configuration, SBs with durations of 2 hours or less may be viable. If there are eventually only priority C or D SBs at your LST range(s) of interest, it may be profitable for you to submit SBs with longer durations.

Tips for More Flexible Scheduling Blocks

This section is particularly relevant for SBs with priority C or D, but also for SBs with priority B and involving the most popular LST ranges or the higher frequencies. Some of these tips may also be useful when preparing SBs with priority A.

More flexibility will increase the chance that a particular SB gets observed. However, if the conditions are too flexible or if the overhead becomes so large that the data cannot be calibrated or yields too little time or u-v coverage on the science target, the data set may not achieve the anticipated science goal. Always ensure that the data set can be calibrated. If there are options to consider, it may be better to choose the option that leans toward a more conservative calibration rather than the option that accrues more observing time on the science target. More conservative calibration will also ensure smoother data reduction.

Tips on how to increase the chance that an SB will be observed:

- Submit the SB early. If the SB is not available when a scheduling gap occurs, it cannot be selected for observation. Gaps can occur at any time, including at the planned start of the array configuration (see the configuration schedule).

- Submit a short SB. Short gaps occur more often than long gaps. Make SBs short and repeat them as many times as desired to accumulate observing time. SBs may now have arbitrary lengths.

- Submit SBs with various durations. It is permissible to submit SBs that, in aggregate, exceed the total time allocated to a program block or a project. Use this to your advantage by submitting SBs with various durations. For example, if a scheduling gap of 1.5 hours is available then compete for it with an SB of duration 1.5 hours instead of an SB with a duration of 1.0 hour. That shorter SB can be used to compete for a later scheduling gap of 1.0 hour. Also, as the pressure from priority A and B SBs drops a few months into a principal configuration, scheduling gaps can sometimes accommodate priority C or D SBs longer than 2.0 hours.

- Break up high and low frequency observations. There is more low frequency time than high frequency time, so it is usaully harder to get observed if the weather (API and wind) limits are very low. If it does not matter if low and high frequencies are observed at the same time it is often advantageous to split observations into low and high frequency blocks.

- Relax the API or wind limits for the SB. For example, if the science target is strong enough for self-calibration then the API limit can be relaxed compared to the default value.

- Widen the possible start LST range(s) of the SB. Especially at low frequencies, consider observing down to the elevation limit of the antennas.

Scheduling Block Life Cycle

Project and Program Block Creation

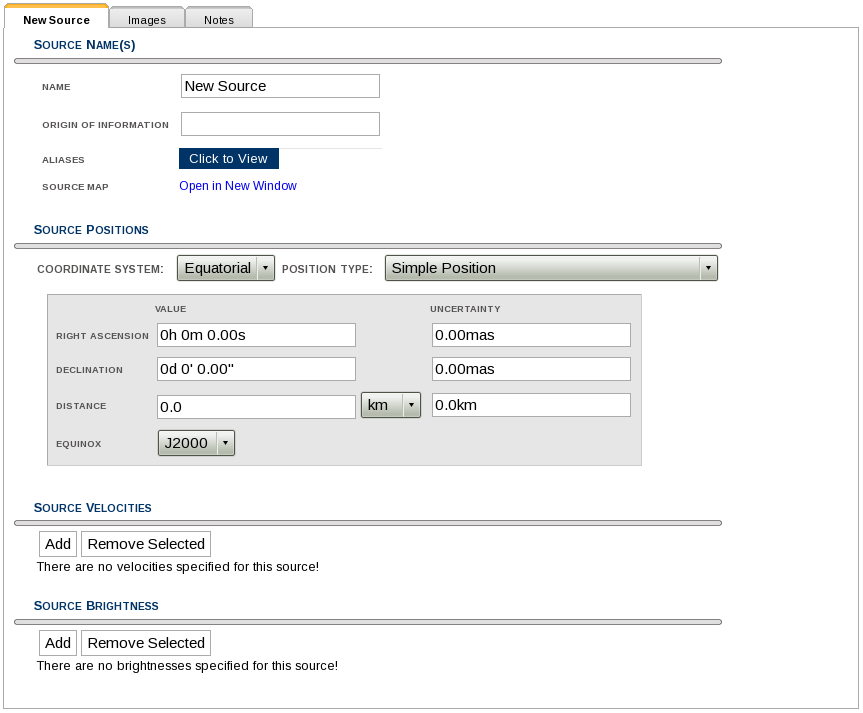

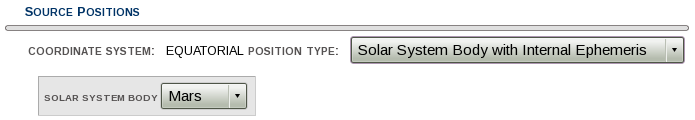

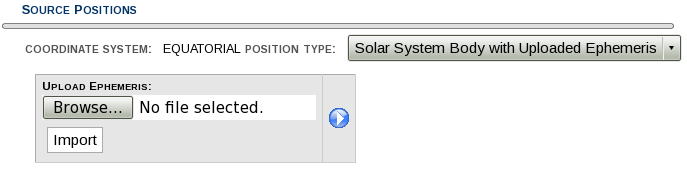

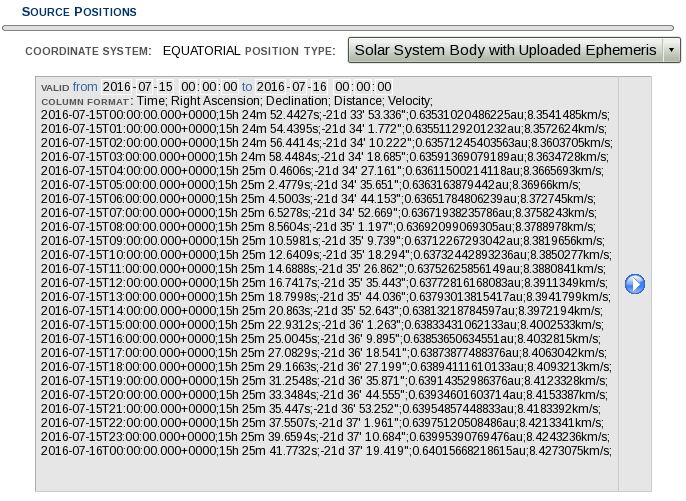

After the approval of a project, the observers are responsible for creating valid Scheduling Blocks (SBs) to achieve their science goals. About one month before the first possible observation, i.e., the start of the requested array configuration in the observing semester, NRAO will create the Project tree with the Program Block (PB) assignments in the Observation Preparation Tool (OPT). Concurrently, the source list is automatically transferred from the Proposal Submission Tool (PST) to the Source Catalog Tool (SCT). If the project consists of observations in more than one array configuration, all PBs will be created at the time of the original import process. Another reminder email will be sent out about a month before observations are anticipated to start in the next array configuration. Once observers have been notified that the OPT has been populated with the Project and PB(s), they may begin creating and submitting valid SBs. Before doing so, it is strongly advised to check whether the import of sources into the SCT have been transferred correctly, e.g., the proper coordinates, epoch, and velocity information (with convention). This is also a good time to create a resource catalog within the Resource Catalog Tool (RCT), also known as the Instrument Configuration tool within the OPT. Once in the OPT, one may also (un)check if an individual on the project would like to receive email notifications for the project, i.e., SB submissions and the operator's observing log emails.

Scheduling Block Creation and Submission

The creation of the SB(s) is the responsibility of the observer(s). The Guide to Observing at the VLA aims to help with this step and contains several suggestions and background information. It is very important for the observer to read through the entire guide, especially the chapter(s) pertaining to their science, e.g., high frequency strategy, low frequency strategy, very low frequency strategy, calibration, polarimetry, spectral line setup, etc. To help observers validate their SB(s) and resource(s), read through the Presubmission Checklists. However, if there is uncertainty regarding the validity of the SB(s), please submit a ticket to the NRAO Helpdesk before submitting the SB(s).

After submission the status of the SB will change from NOT_SUBMITTED to SUBMITTED. The OPT will generate an SB submission email to alert the VLA data analysts to perform a validity check soon thereafter. Note that this is not a science check for, e.g., correct frequencies or spectral line setup, but merely checking the requirements and logistics so it will not disrupt observing. If a submitted SB requires corrections, it can be canceled (unsubmitted), changing the status back to NOT_SUBMITTED.

If the VLA data analysts find any problems with the submitted SB(s), the observer will be notified (preferably through the NRAO Helpdesk) and may be asked to cancel, improve, and/or submit the improved SB(s). Otherwise, when there are no logistical problems apparent, the VLA data analysts will approve the SB(s) for observing, thereby changing the status of the SB(s) to SCHEDULABLE for observing.

At rare occasions, for experienced observers in cases where SBs need to be able to execute very rapidly after submission, e.g., for a target of opportunity, the observers may be given special permission to self-approve their SBs at the time the PBs are created. There will be no validity check of the SB submissions by the VLA data analysts, and the responsibility of the successful execution remains entirely with the observer with the understanding that no make-up time will be granted for unsuccessful observations.

Scheduling Block Observation and Archiving

SBs for observation are drawn from a weighted pool of SCHEDULABLE observing blocks, according to the guidelines explained elsewhere in this guide. When an iteration of an SB gets queued, a copy is created known as an Execution Block (EB). The EB lives as QUEUED, RUNNING, PENDING FAILURE or PENDING COMPLETION before the final EB status of FAILED or COMPLETED. Note that these short-lived intermediate EB status designations are merely helpful to the operators and staff. After the successful execution (observation) of each iteration of the SB, the observer will be notified of the successful completion of an iteration of the SB. The status of the SB will remain SCHEDULABLE as long as there are remaining iterations. The successful completion of all repeat-iterations specified in the SB will mark the status of the SB as COMPLETED. The observer can retrieve the individual SB executions of the data from the NRAO data archive. Data will be proprietary to the original observers typically for one year after the last observation taken for the project; after which the data becomes public and accessible to all archive users.

Occasionally, mostly for logistical reasons, during the scheduling of observations in the dynamic scheduling process, the operator may defer an SB to ON HOLD. This is a very short-term status and the operator or NRAO staff will quickly release the SB back to the queue or take other actions to resolve any issues. In some cases, for miscellaneous reasons, the execution of an SB may not complete. Scheduling blocks with an EB having a status of FAILED will be investigated and, if appropriate, the observer will be contacted for follow up. An SB with a FAILED execution block typically triggers a re-observation at a later time (see also Re-Observation of FAILED Scheduling Blocks below).

Scheduling blocks that have not been observed, or have remaining repeat iterations at the end of the observing period allocated to the project (typically at the end of the allocated array configuration(s) or observing semester), will be given the status of EXPIRED and will be removed from the active observing queue. Once COMPLETED or EXPIRED, the SB becomes read-only and thus cannot be unsubmitted or edited. However, the SB can be read and (partially) copied to a new SB in a new or otherwise active PB which can then be modified for new observations.

Scheduling Block Status Monitoring

Observers who have switched on their email notifications in the Project will receive emails for each SB of the project when the status changes to SUBMITTED, or back to NOT_SUBMITTED. Currently, we are working on a notification when a SB becomes SCHEDULABLE or EXPIRED.

Anyone on the project can monitor the status of the SBs in the project by logging into the OPT. The status summary of all SBs in a program block (PB) is viewed by selecting the PB level of the Project tree. Here the number of anticipated executions (or counts), LST start range, and the wind and API constraints are listed. For each execution of an SB, including repeat executions, the PB level of a Project contains a table of Execution Blocks (EBs) listing the corresponding SB ID, status, duration, start and finish date/time (in LST and UTC), initial API and wind readings (which are likely to change during the observation) can be found below the table of SBs. The same information can be found under the Executions tab within an SB. This information is added after an SB is executed, and the corresponding EB is created.

Observers may monitor a webpage setup to display a list of what has been observing on the VLA for the last 12 hours (updates every 10 minutes).

Re-Observation of FAILED Scheduling Blocks

Occasionally, an observation will fail for any of a number of possible reasons. If a project is in the General Observing category, it will be placed back into the dynamic queue for possible re-observation when conditions allow. Those projects in the Shared Risk and Resident Shared Risk categories may not be re-observed if they fail due to problems with the shared risk/resident shared risk component(s) of the observation. If observers believe that an observation should be failed after inspecting their data they should submit a ticket to the NRAO Helpdesk as soon as possible and in all cases prior to the expiry of the period of eligibility for scheduling.

Dynamic Scheduling Considerations

Introduction to Dynamic Scheduling

Most scheduling blocks (SBs) are observed dynamically, based on factors that NRAO controls and on factors that the observer controls. Such dynamic scheduling enhances science data quality and the array's ability to discharge time-sensitive science. On rare occasions, an SB that requires coordinated observations with other telescopes will be scheduled on a fixed sidereal date. If you have questions regarding the scheduling of your SBs please contact the VLA schedulers via email at schedsoc@nrao.edu or via the NRAO Science Helpdesk using the VLA Scheduling Support department.

NRAO staff use the Observation Scheduling Tool (OST) to examine the current observing conditions and the queue of SBs submitted for the current array configuration. The observing conditions are quantified by the RMS phase measured with the Atmospheric Phase Interferometer (API), the wind speed, and the sunrise/sunset time. The OST then applies heuristics to create a schedule, which is just a time series of optimal SBs. The first optimal SB in the series is then sent off for execution by the monitor and control system. Just before that execution completes, the OST again applies heuristics to create a new schedule.

The heuristics used by the OST include the scheduling priority (A, B, C or D) assigned by the Time Allocation Committee or Director's Discretionary Time Committee and, for TAC reviewed proposal, the linear-rank score assigned by the Science Review Panel. The heuristics also include SB attributes under observer control, specifically its duration, weather constraints (API and wind limits), observing bands, range of LST start times and, optionally, an earliest start date and a request to avoid sunrise/sunset.

Dynamic scheduling obviously means that the observer does not know when the observations will occur. This must be kept in mind when preparing an SB. In particular, the observer should check that none of the possible LST start times create problems with antenna wraps and the scans of the flux density scale calibrator. These topics are discussed in more detail below.

Doppler Correction

For some spectral line setups, Doppler correction (position and velocity) should be applied. The benefit of Doppler Setting, since the VLA is dynamically scheduled, is that it calculates the sky frequency at the beginning of an SB and keeps this fixed for the duration of the SB. Doppler Setting can be specified for each individual baseband in the OPT, removing the burden to do this for each possible observing run by the observer. For more details, refer to the Doppler Correction section within the Spectral Line guide.

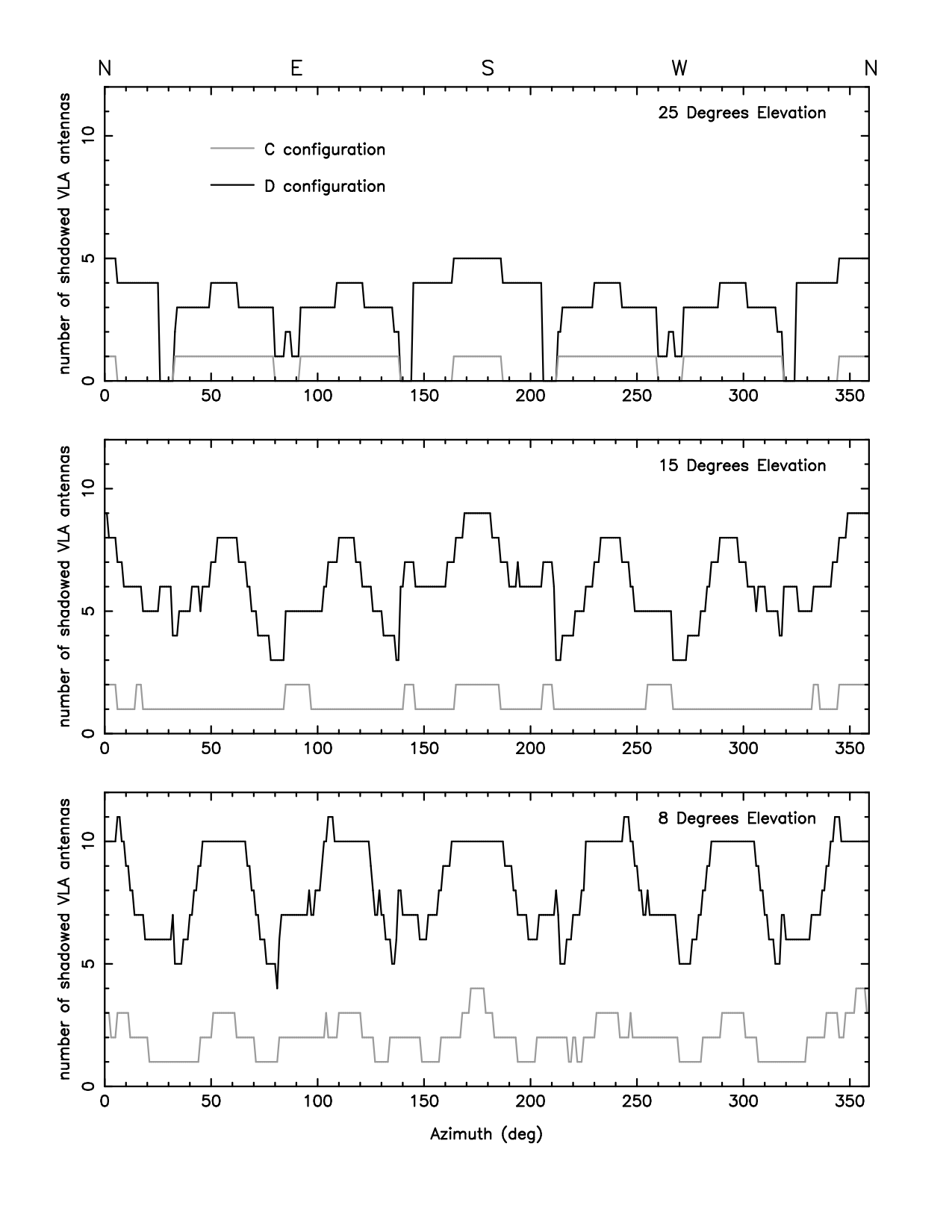

Antenna Shadowing

An antenna is shadowed when its line-of-sight to the source is partially or fully blocked by another antenna in front of it. The shadowed antenna will collect less radiation from the source than if it had not been shadowed, reducing the sensitivity on the baselines to that antenna. Shadowing is more likely to occur when sources are at low elevation and when the antennas are in more compact configurations. The OPT will report, per scan, the maximum amount of shadowing, if any, will occur according to the location in the sky of the target and the configuration of the observations. D-configuration is affected by shadowing more than the other configurations because the antennas are at their closest proximity to each other. If you select "Any" configuration, the OPT will calculate the worst-case scenario by assuming the D-configuration to calculate shadowing.

If any calibration scans will be shadowed for any of the valid LST start times, we recommend increasing the observing time of the calibration source to account for the loss of sensitivity. Table 2.3.1 shows the amount of shadowing in respect to the fraction of an antenna that is blocked with the corresponding loss of sensitivity. All shadowed baselines will be similarly affected. Note that the loss of sensitivity is not linear with the fractional shadowing.

| Shadowing | Fraction of Area Blocked | Baseline Sensitivity Loss |

|---|---|---|

| 1 m | 0.01 | 0.5% |

| 5 m | 0.10 | 5% |

| 12.5 m | 0.39 | 22% |

| 18 m | 0.64 | 40% |

| 25 m | 1 | 100% |

Avoiding antenna shadowing during the D-configuration relies on the azimuth of the antennas, which is dependent on the location of the source and the LST start time. Therefore, to guarantee no more than a single shadowed antenna, restrict the elevations, if possible, to >40° for D-configuration and >25° for C-configuration. Shadowing is worst along the azimuths of the arms (in both directions), so has a six-fold symmetry. See Figure 2.3.1 below. Note that the maximum elevation (in degrees) for your target is its Declination plus 56°, so it may not be possible to avoid any shadowing for sources at Dec < -16° or Dec < -31° for D and C configuration, respectively.

Antenna Wraps

Before we dive into the details of antenna wraps, the OPT will now recommend an LST start range based on selected elevations (minimum and maximum limits) for a Scheduling Block (SB) containing all appropriate scans, including, but not limited to, science target(s), complex gain calibrator, flux density scale calibrator, etc.. The recommended LST start range(s) may also include suggested antenna wrap requests. For more details, refer to the following sections under the OPT manual: Create an SB and Scans and Dynamic LST Validation Tab.

- Tip: The suggested antenna wrap per LST start range should be double checked by selecting the wrap on the first few scans (roughly the first 10min) and then check the SB on the Static Report tab and the Dynamic LST Validation tab. In most cases, only one wrap should be used per LST start range. For example, if the OPT recommends two LST start ranges with opposite antenna wraps, we recommend making a copy of the SB to make use of each LST start range and corresponding antenna wrap. If you do not want both SBs to run, you may link them so only one is observed while the other is expired. Refer to the OPT manual on how to link SBs.

Introduction

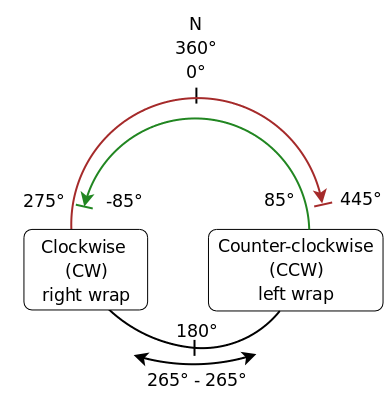

To help avoid confusion, we will define some terminology. For a visualization of these terms, refer to the wrap diagram below (Figure 2.4.1).

| Wrap Type | Definitions |

|---|---|

|

Clockwise (CW) Right or Outer |

When looking down at the VLA from above, the antennas on a CW wrap would appear to be tracking in azimuth in a CW direction from 180° real Az. |

|

Counter-clockwise (CCW) Left or Inner |

When looking down at the VLA from above, the antennas on a CCW wrap would appear to be tracking in azimuth in a CCW direction from 180° real Az. |

| North | This term is used where the CW and CCW wraps overlap between 275° and 85° real Az, passing through 0° / 360° (north) (CW: 275° to 445° (85° real Az) / CCW: −85° (275° real Az) to 85°). |

| South | This term is used for the unambiguous section of the wraps where there is no preference over the use of either CW or CCW wraps. The south wrap is from 85° to 275° real Az, passing through 180° (south). |

During the observation of a single source, or by switching from one source to the next, the antennas are continuously changing their pointing toward different directions in the sky. The cables for power, communication, and data transfer have a limited length and wrap around the rotation (azimuth) axis of the antenna while the antenna moves. Software directs the antenna movements to prevent them from tightening and snapping when the cables reach the azimuth cable wrap limit, i.e., when they have wrapped ±265° either direction (CW or CCW) from the south (at 180° real azimuth). At a wrap limit, instead of continuous tracking during a scan or directly moving to the next scan at a scan boundary, the antennas will move the opposite long way while unwrapping the cables. As the azimuth slew rate is 40°/min, a full 360° azimuth unwrap will take up 9 minutes (plus some settling time) of unusable observing time (this can vary slightly per antenna). It is important to avoid such a situation and pay attention to the antenna azimuth and wrap during the observation, which means paying attention to the wrap when the azimuth of the scan in the Schedule Summary reports if the scans approach 85° and 445°, or when the scan sequence crosses −85° and 275° azimuth (see Figure 2.4.1 below). Perhaps experiment with different azimuth (and elevation) starting positions to investigate the effect (and starting slew times) for a particular scheduling block (SB).

Another inconvenient wrapping situation appears when observations near zenith (elevations larger than about 80°) switch between sources on different azimuth wraps. This happens when a target and calibrator are close to, but on opposite sides of 34.1° (34°04′43.497′′) Declination (latitude of the VLA). The OPT will show slew times much longer than expected for the angular source separation, and indicate an azimuth wrap (CW or CCW) on only one of the sources in the reports of the scan list. So even if a calibrator may be a bit further away or less strong, it may be the better option when it is on the same side of zenith. Experiment with different LST start times to investigate the effect for a particular SB if no suitable calibrator can be found on the same side of zenith.

The most important antenna wrap issue arises at the start of the SB as the wrap chosen determines the wrap for the rest of the observation (if not specified in further scans). This wrap should also align the azimuth of antennas combined from previous different subarrays at the start of observing. At the end of the previous program the antennas (or subarrays of antennas) are left pointing in a direction that is dependent on the previous program, and may be any azimuth between −85° and +445°. When the antennas slew toward the first source in the SB, there are two options: clockwise (CW, also known as Right or Outer) or counterclockwise (CCW, also known as Left or Inner); see Figure 2.4.1. In dynamic scheduling, the software will choose the shortest slew to the first source unless otherwise specified in the antenna wrap option in the first scan(s) in the SB. This default software choice may or may not be the optimum case for the observations. To avoid problems, if any of the scans in the SB are observed outside the range between +85° and +275° in the south, then specify the antenna wrap at the start-up sequence (roughly the first 10min) to be assured that thereafter the wraps in the reports listing correspond to the actual wraps during the observations. Only when all scans in the SB remain between, or completely avoid the range of +85° and +275° azimuth during any of the start times specified in the LST start range, there is no explicit need to specify any wrap. That is, observations entirely on the south wrap or entirely on the north wrap should be fine, but if you include any of the common standard flux density scale calibrators (i.e., 3C48 or 3C286) most likely the observation will include LSTs where these sources are on the other wrap.

Summary of Wraps

When to request an antenna wrap: Unless the first source (i.e., setup scan(s) and the first standard observing or reference pointing scan) is always in the unambiguous (south) part of the wrap (85° ≥ Az ≤ 275°; see Figure 2.4.1 below) during any LST start time within the set range, then you should request an antenna wrap for each scan of the start-up sequence (generally the first 10–15 minutes of the SB). If the SB starts with either 3C286 or 3C48, then an antenna wrap should be selected and continue to specify that wrap for the startup sequence of the SB. Be aware that when 3C286 or 3C48 rise and set they cross the ambiguous (275° ≥ Az ≤ 85°; see Figure 2.4.1 below) part of the wrap, which can cause problems with unwrapping to the next source (i.e., the complex gain calibrator), so there may not be any time on the first complex gain calibrator scan or the first science target scan.

Which antenna wrap to choose: Look at the first scan under the Schedule Summary report to check if there is an unwrap issue (275° ≥ Az ≤ 85°) for all times in the LST start range. Follow how the azimuth evolves during the observing block and whether it crosses the 275°/85° boundaries. Select a wrap which takes the antennas in a direction so there is plenty of room for the antennas to move without having to unwrap again; check the LST start range by stepping through at least every hour, making sure that all scans have plenty of on source time (no less than 20sec for standard observing and no less than 2min30sec for reference pointing). Sometimes the LST start range will need to be adjusted to avoid an unwrap.

Antenna Wrap Caveats: When the schedule summary reports a calculated wrap CW or calculated wrap CCW, do not assume that the calculated wrap will be the starting wrap. The calculated wrap is also a good indication that a wrap should be set, but not always in the calculated direction.

Addressing Both Wraps: When an SB can have two LST start ranges to cover the rising and setting of sources, we recommend submitting two SBs to cover the two LST start ranges and their corresponding antenna wraps. For more details on how to create linked SBs, refer to the FAQs page or the Linking SBs section of the OPT manual.

Antenna Wrap Bugs in the OPT:

- In some circumstances, and only for the first and second scan, there is a discrepancy in the reporting of the telescope azimuth. This is apparent when an SB starts on a source that is always in the north (Dec > 34°) using the default of azimuth 225° (i.e., in the south). In this case, the OPT may report a confusing starting azimuth on the first scan and an azimuth jump and/or a wrap change for the second scan (even if it is the same source). This bug can be ignored and no wrap need be set.

- A slightly different wrap display bug in the Reports page, is where the first and second scan on the north wrap may differ by 360°.

Detailed Guide

Wrap Diagram

Figure 2.4.1 shows the antenna wrap diagram; this diagram is very helpful in resolving wrap issues. Use this diagram in conjunction with the azimuth column in the scan listing of the Schedule Summary Report table for different LST start times to investigate whether any wrap issues may occur. Often wrap issues will appear when the standard flux density scale calibrator sources 3C286 and 3C48 are scheduled to be observed at rise and/or set at either limit of the LST start range, or when they might be observed during culmination at zenith. That is, many observers should take note to avoid any problems by adhering to the antenna wrap guidelines.

It should be noted, for completeness, that the online software monitors the azimuth of the antennas constantly (i.e., on time scales of seconds; not per scan). As soon as the actual azimuth of a particular antenna hits the −85° or +445° azimuth limit, the antenna will be directed to unwrap and slew in the opposite direction to catch up with the observation instruction. As this happens at the actual azimuth (after the global pointing model and possible additional reference pointing corrections are applied), the time at which a specific (the first) antenna might unwrap may be different from another antenna (the last) by a minute or so. To avoid unwrapping antennas at different times, make sure the scans do not start or stop very close to these azimuth limits for any of the potential LST start times of the SB.

|

West |

|

East |

| Figure 2.4.1: VLA wrap diagram with Azimuth conventions and readings and the cable wrap limits. Clockwise wrap goes over West (red; outermost curve from the bottom to the top of the spiral) and Counterclockwise over East (green; innermost curve). South (unambiguous) wrap is between azimuth +85° and +275° (black; bottom of the spiral) and North (ambiguous) wrap is in the area at the top, between −85° and +85° or +275° and +445°. | ||

Antenna Wrap & Elevation Considerations

A source is rising when the LST (modulus 24h) is less than the RA of the source. A source is setting when the LST is greater than the RA of the source. Note that for this reasoning, the RA and LST (range) should be within 12h of each other to properly determine rise or set. If the difference is larger, add 24h to either the RA or LST range values, whichever has the lower value in the SB.

- If all of your sources, targets, and calibrators have Declinations below about 8.5°, they are all observed in the south wrap and will never reach the ambiguous wrap region: no wrap setting is needed. Note that this almost never happens as you want to include one of your flux density scale calibrators and all have a Declination larger than 8.5°. If any of the sources has a Declination very close to 8–9°, this rule of thumb may not apply and more care should be taken in checking the observing schedule. This 8.5° limit assumes observations all the way down to the elevation limit of 8°. For observations using higher elevation limits, the 8.5° Declination rule becomes a higher-than-nine Declination rule, depending on the actual elevation limit:

|

|

Elevation limit |

8° | 10° | 15° | 20° | 25° | 35° | 45° | 60° | 90° |

l=latitude (34o04' for VLA) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Highest Dec. on the south wrap (Az=85°), i.e. never on north wrap | +8°35' | +9°41' | +12°24' | +15°02' | +17°35' | +22°21' | +26°34' | +31°25' | +34°04' | sin(d)=sin(l)sin(e)+cos(l)cos(a)cos(e) or for VLA approximately sin(d)=0.5602*sin(e)+0.0722*cos(e) | |

| Lowest observable Dec. (Az=180° south) | -48° | -46° | -41° | -36° | -31° | -21° | -11° | +4° | +34° |

d=e+l-90, or for VLA d=e-55o56' |

|

| Circumpolar Declination (on north wrap) | +64° | +66° | +71° | +78° | +81° | (+90°) | d=e+90-l, or for VLA d=e+55o56' | ||||

- If all of your sources (targets and calibrators) have Declinations above about 34°, they are all observed in the north wrap and will never use the south wrap region: no wrap setting is needed. Note that this is unlikely unless you use 3C147 as your flux density scale calibrator or 3C295 (in the case you observe only below 2 GHz in D configuration). If any of the sources has a Declination very close to 34°, this rule of thumb may not apply and more care should be taken in checking the observing schedule.

- If your first source has a Declination of less than about 34° and is rising at the start of the observation, set the starting sequence wraps (first 10–15 minutes worth of scans at the start of the block) to CCW (left). If the first source is setting, set the wrap to CW (right).

- If your first source has a Declination of more than about 34° (i.e., it will be observed in the north), then there are two options that will only make a difference once the next source in the sequence has a Declination below about 34° (otherwise you can use the second rule above). If that next southern Declination source at the time of the observing LST (i.e., the starting LST time plus the duration of time into the observation) is rising then set the starting sequence (first 10–15 minute worth of scans at the start of the block) wraps to CCW (left). If this southern source is setting, set the beginning sequence wraps to CW (right).

Always make sure to check the wraps in the Reports tab of the SB in the OPT. If in doubt or confused, please leave the wrap designation to "No Preference" and consult the NRAO Helpdesk.

For more detailed information on setting antenna wraps, see the section How to Proceed below.

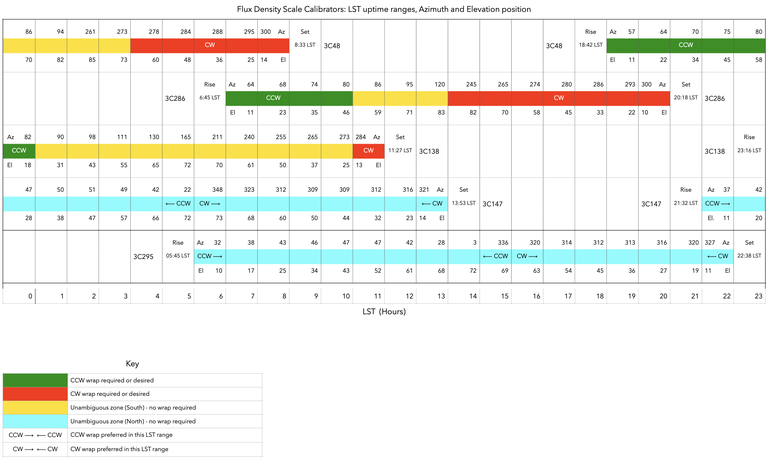

Wrap Issues & Standard Flux Density Scale Calibrators

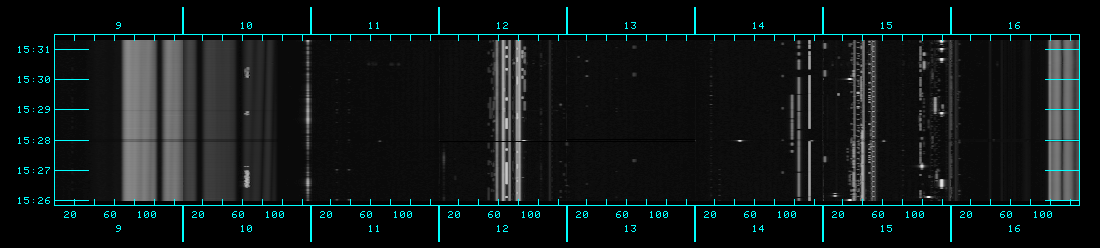

The default standard flux density scale calibrators for the VLA, 3C286 (J1331+3030) and 3C48 (J0137+3309), are nicely separated by about 12 hours in Right Ascension (RA) but, unfortunately, have two major inconveniences. First, their Declination is almost the latitude of the VLA (34.1°), which causes them to culminate almost at zenith on the southern wrap and, second, while they are mostly in the southern wrap, they rise and set in the northern wrap. Catching these flux density scale calibrators in short SBs may be difficult for target observations in certain regions distant from these calibrators on the sky. Therefore, it quite often happens that the flux density scale calibrator is observed in these dynamic SBs when a flux density scale calibrator just rises or just sets, where wrap issues may become a problem for targets on the southern wrap. For targets on the northern wrap, even though the flux density scale calibrators may be high in the sky, it decreases the usable LST start range to place the flux density scale calibration scans if wrap issues are to be avoided. See Table 2.4.2 and Figure 2.4.2 for details.

Table 2.4.2: Wraps and wrap limits for Standard Flux Density Scale Calibrators at the VLA

| North Wrap | South Wrap | North Wrap | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rise at | Az= 85/445° | Az= −85/275° | Set at | |||||

| Az | LST | LST | El | El | LST | LST | Az | |

| 3C48† | 55/415° | 18:42 | 23:53 | 68° | 68° | 03:23 | 08:33 | −56/304° |

| 3C286 | 59/419° | 06:45 | 10:53 | 57° | 57° | 16:09 | 20:18 | −58/302° |

| 3C138* |

75/435° | 23:16 | 00:29 | 23° | 23° | 10:13 | 11:27 | −75/285° |

† 3C48 has varied in flux density over the last few years, but appears to have settled down.

* The flux density scale calibrator 3C138 is currently undergoing a flare. As of January 2025, the change in flux density is greater than 10% at all frequencies greater than 4 GHz (i.e., C-band). At present, the magnitude of the flare is approximately a factor of 2 at K-band, 3 at Ka-band, and 4 at Q-band. Monthly monitoring observations are available for investigators that require an accurate flux density scale when using 3C138. These observations are publicly available in the archive under the project code TCAL0009. A table of scaling factors per band per month from February 2021 onward has been provided.

| Rise at | Easternmost Azimuth |

Westerenmost Azimuth |

Set at | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Az | LST | LST | Az | |||

| 3C147 | 33/393° | 21:32 | 51/411° | −51/309° | 13:53 | −33/327° |

| 3C295‡ | 30/390° | 05:45 | 48/408° | −48/312° | 22:38 | −30/330° |

‡ Disclaimer: CASA does not have a flux density scale model for 3C295.

|

|

Figure 2.4.2: Antenna wrap a a function of LST for the standard flux density scale calibrators. (Click image for a larger view.) |

When the source is observed at an LST shown in green in Figure 2.4.2 (above), the source is in the south and typically no wrap issues arise. When the LST is red, the source is in the northern wrap and either a CCW (left; at rise) or a CW (right; at set) wrap should be specified in the scan. For 3C147 and 3C295 the wrap should be specified as well; the wrap, however, will depend on the efficiency to reach the other sources specified in the schedule. The yellow LST regions are when the sources, 3C48 and 3C286, are at an elevation above 80° and should probably be avoided during high frequency observing. (Note, low frequency observing can observe up to 85° in elevation, too much higher in elevation can cause antenna wrap issues.)

How to Proceed

Initially, it is best not to worry about the antenna wrap until the SB has been created. Then extensively check the azimuth of the scans in the SB for all LST start times in the anticipated LST start time range. This action will reveal if any wrap issues occur for some or all of the possible LST start times.

Aside from any wrapping issues, remember that 3C286 and 3C48 culminate near zenith. To avoid pointing problems at high elevations (≥ 80°) during high frequency observations, it is probably best to avoid having scans for these flux density scale calibrators during the LST range 12:47–14:15 for 3C286 and the range 00:50–02:25 for 3C48. Restrict the LST start range so the scans with 3C286 and/or 3C48 will not happen for these LST times, or perhaps even split the LST start range in two (or more) non-overlapping LST start ranges in the INFORMATION tab of the SB. Ideally, one would want to observe the flux density scale calibrator at about the same elevation as the target sources to obtain a more accurate flux density, especially at the higher frequencies. However, this is hard to plan and not always manageable with dynamic scheduling: it would require a restricted LST start range which would decrease observing chances. Another suggestion, for similar reasons, is to try and observe the flux density or bandpass calibrator when the target source passes through zenith (if its Declination is near 34°).

Assuming that the target sources are not scattered all over the sky (e.g., for a survey), there are essentially four cases when using 3C286, 3C48, and/or 3C138:

- 3C286/3C48 can only be observed between rise and culmination in the (South)East: The target source is leading the flux density scale calibrator in the south or north of zenith, typically by up to 6 hours in RA (otherwise the other flux density scale calibrator is more likely to be chosen).

- For Dec < 34.1° the target source will be south of zenith and set after the flux density scale calibrator rises. There should be no wrap issues if the wrap directs the antennas to observe the flux density scale calibrator in the CCW (left) wrap or when the LST start range is limited such that the flux density scale calibrator scan can only happen after the LST time for Az = 85°/445° for that flux calibrator in the table above. Typically, the flux density scale calibrator is observed at the end of the SB.

- For Dec > 34.1° the target source will be north of zenith and stay on the north wrap. There should be no wrap issues if the flux density scale calibrator is observed before the LST time for Az = 85°/445° for that flux density scale calibrator in the table above. Typically the flux density scale calibrator is observed whenever the scan can fit in the LST range for the eastern north wrap, i.e., between rise time LST and the LST time for Az = 85°/445° for that flux density scale calibrator in the table above.

- 3C286/3C48 can only be observed between culmination in the (South)West and set: The target source is trailing the flux density scale calibrator in the south or north of zenith, typically by up to 6 hours in RA (otherwise the other flux density scale calibrator is more likely to be chosen).

- For Dec < 34.1° the target source will be south of zenith and rise before the flux density scale calibrator sets. There should be no wrap issues if the wrap directs the antennas to observe the flux density scale calibrator in the clockwise CW (right) wrap or when the LST start range is limited such that the flux density scale calibrator scan can only happen before the LST time for Az = −85°/275° for that flux density scale calibrator in the table above. Typically, the flux density scale calibrator is observed at the start of the SB.

- For Dec > 34.1° the target source will be north of zenith and stay on the north wrap. There should be no wrap issues if the flux density scale calibrator is observed after the LST time for Az = −85°/275° for that flux density scale calibrator in the table above. Typically the flux density scale calibrator is observed whenever the scan can fit in the LST range for the western north wrap, i.e., between the LST time for Az = −85°/275° and set time LST for that flux density scale calibrator in the table above.

- 3C286/3C48 can be observed throughout the SB duration for all LST start times: For this case one would probably choose whether to put the flux density scale calibrator close to the start or close to the end of the SB. Placing it in the middle would not minimize the chances of culminating during the SB and introduce wrapping issues for northern wrap target sources. By placing the flux density scale calibrator observations at the start or the end of the SB, either of the above cases would apply as guideline on how to proceed. Continue checking the azimuth for different LST start times and perhaps even change the strategy on where to place the flux density scale calibrator observations.

- More complicated than any of the three above: If the SB cannot be converted to a simpler case by grouping source scans to the same wrap and/or choosing the flux density scale calibration scans at the start or end of the SB, this case may become more like a trial-and-error approach. Usually this is not a problem; however, if it remains, continue checking the azimuth for different LST start times, maybe limit the LST start range even further and/or perhaps even change the strategy on where to place the flux density scale calibrator observations.

After creating the SB, please check the wraps and look out for possible issues for all possible LST start times in the LST start range before submitting the SB. This may be time consuming but will prevent surprises during observing and in the data. When setting a wrap at the start of the SB, please continue to specify the same wrap during the start-up sequence, i.e., for all the scans that make up the first 10–15 minutes for the SB to force it to be effective.

Note that the slew to the first source, and the calculated wrap it chooses is calculated from the assumed starting position as specified in the INFORMATION tab of the SB. By default, this starting position is pointing toward the south; but the actual starting position is from wherever the previous program has left the antennas pointing (anywhere from azimuth −85° to +445°), and not necessarily the same direction for each antenna. Playing around with the starting azimuth may help to determine the maximum slew time for the worst case scenario and whether different wraps are possible for different LST start times. For testing maximum slew times at the start of the observation the worst cases arise, with the wraps specified as suggested above:

- When one or more antennas are at Az = −85° and the SB is started at the latest possible LST start time of the LST start range, and;

- When one or more antennas are at Az = +445° and the SB is started at the earliest possible LST start time of the LST start range.

For high frequency observations, there should be at least 2min30sec on source time in the reference pointing scan in addition to the worst case slew time. And to complicate it even further, the worst pointing case may not be at the worst starting LST.

Please ask the NRAO Helpdesk if you need assistance.

Avoiding the Sun

The Sun is a bright and variable radio source and can be a problem for VLA observations at all frequencies if it is near the target source. Phase fluctuations and elevated system temperatures will result when observing too close to the Sun. This section gives guidelines on how far sources should be from the Sun as a function of observing band at the VLA, as well as some links to tools to help in planning observations. Please note that these guidelines should not be confused with avoiding daytime observing for RFI reasons, or avoiding sunrise and sunset for phase stability reasons.

Currently, the OPT does not look for or flag SBs containing sources which could be observed too close to the Sun. The Observation Scheduling Tool (OST) will provide a Sun proximity message to the VLA operators to note in the observing log. However, this does not mean the operator will not proceed with a non-solar observation if the sources are too close or behind the Sun. It is the responsibility of the observer, to monitor both if and when their sources will be too close to the Sun and the activity of the Sun. The VLA Sun & Moon Distance Check Tool can help determine if and when a source will be too close to the Sun. This tool also gives the distance to the Moon, although typically the Moon is not a problem unless it is very nearby (within a few primary beam FWHMs).

Solar Activity Webpages

- NOAA Space Weather

- Long Wavelength Array (LWA) provides near real-time and archival solar activity (< 100) MHz all-sky observations.

Handling SBs with Sources Near the Sun

If any of the sources in an SB are too near the Sun (especially if it is particularly active), then there are a couple ways observers may address this:

- On the Information tab of an SB, you may set an earliest/latest UT start date/time to avoid dates when the sources will be too near the Sun. This field can be edited at any time, i.e., before/after SB submission and when the SB is schedulable (in the observing queue).

- You may also unsubmit the SB. If you choose to unsubmit, please be sure to resubmit when appropriate. We will not know why the SB was unsubmitted and will not preemptively re-submit when solar activity has subsided.

Recommended Observing Distances from the Sun

Table 2.5.1 shows the minimum distance from the Sun for 10° phase errors (Φ), assuming the longest baselines can be tolerated. Depending on the solar activity of the Sun, the acceptable observing distance will increase.

Note: We have noticed an increase of solar activity causing problems with phases in the data. Consider a more conservative distance from the Sun than what is list in the table. For example, L-band in D and C-configuration may want to consider observing ~10-20° from the Sun.

The numbers in table 2.5.1 were calculated via:

\[R_{deg}≈\left(\frac{7\lambda_{cm} * B^{0.29}_{km}}{\phi_{deg}}\right)^{0.71}\]

where Bkm is the baseline in km, λcm is the frequency in cm, and Φdeg is the phase error in degrees. Details on how this equation was derived are in VLA Test Memo 236, "How close to the Sun should we observe with the VLA?" Another useful memo is EVLA Memo 136, "EVLA Measurements Close to the Sun: Elevated System Temperatures."

More details about the effect of the Sun on VLA observations may be found in the Low Frequency and Very Low Frequency strategy guides.

| Rdeg | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Band | λcm |

A (36km) |

B (11km) |

C (3km) |

D (1km) |

| Q | 0.7 | 3° | 3° | 3° | 3° |

| Ka | 1.0 | 3° | 3° | 3° | 3° |

| K | 1.3 | 3° | 3° | 3° | 3° |

| Ku | 2.0 | 3° | 3° | 3° | 3° |

| X | 3.5 | 4° | 3° | 3° | 3° |

| C | 6.2 | 6° | 5° | 4° | 3° |

| S | 10 | 8.3° | 7° | 5° | 4° |

| L | 21 | 14° | 11° | 8° | 7° |

| P | 90 | 40° | 31° | 30° | 30° |

| Table 2.4: Short distances have been rounded up to 3°; distances less than this should always be avoided. P-band at C and D-configurations have been rounded up to 30° to minimize the impact of the Sun on these observations. Therefore, distances less than these should always cause concern, and greater distances may be required depending on the observation and the activity of the Sun. | |||||

Weather Constraints

The Observation Scheduling Tool (OST, aka, dynamic scheduler) uses the current Atmospheric Phase Interferometer (API) and wind speed, as well as the predicted wind speed when deciding whether to run an observation, i.e., a Scheduling Block (SB). If the API, current or future wind speeds are above the constraints set in the SB using the OPT then the SB will not be selected. This can make it difficult to observe high frequency SBs.

Wind Limits

The wind speed limit is based on the fact that wind will push the VLA dishes around causing the primary beam to move on the sky. At higher frequencies the primary beam is smaller and so it is easier to move a dish enough to move the target out of the center of the primary beam, therefore the wind speed limit is lower at higher frequencies. Wind speeds higher than the limits will cause the amplitudes to vary which cannot be calibrated after the observation.

Atmospheric Phase Limits

The recommended API limits are based on estimates of the maximum API limit assuming that the science target could not or should not be self-calibrated. If the science target can be self-calibrated then the API limit can be much higher giving the SB a greater chance to be observed. Starting in December 2022 there are two possible Atmospheric Phase Limits (APLs) to choose from depending on whether or not the science target can be self-calibrated.

The following table lists the default weather constraints available in the Observation Preparation Tool (OPT) for each observing band. An observer may choose between the conservative APL or the less conservative self-calibration APL. The wind limit will remain the same between either APL choice.

|

Observing Band |

Wind (m/s) |

Conservative APL (degrees) |

|

Self-calibration APL (degrees) |

| 4, P, L | Any | Any | Any | |

| S | Any | 60 | or | 120 |

| C | Any | 45 | or | 90 |

| X | 15 | 30 | or | 60 |

| Ku | 10 | 15 | or | 30 |

| K | 7 | 10 | or | 20 |

| Ka | 6 | 7 | or | 14 |

| Q | 5 | 5 | or | 10 |

How to Choose the APL for Your SB

Choose the lower (conservative) limit if:

- The science target is too faint to self-cal (see below), or

- The flux density of the science target is unknown and likely faint, or

- There is a scientific reason not to self-calibrate, e.g., when the scientific goal is to perform astrometry

Choose the higher (self-calibration) limit if:

- It is desirable to self-calibrate the science target, and

- The signal to noise ratio (SNR) of the science target is > 3 in a solution interval using the subband width (for continuum) or the anticipated line/channel width (for spectral line) for a single baseline and polarization.

- a solution interval (solint) should be based on how fast the atmospheric phases are likely to be changing and therefore shorter for higher frequencies and longer baselines.

- for a 25 antenna VLA the SNR of the target peak flux density/rmssolint should be ≥20

Examples

- Example 1: The science target is a compact source with a peak flux density of 15mJy/beam. Observing occurs in A-configuration at Ka band continuum. Should we use the higher APL?

- Estimate the solint. The recommended calibration cycle time for A-configuration and Ka band is 3 minutes so we assume that the atmospheric phases will vary faster than that with the higher APL (which allows for observations at less favorable weather during the observation). So let's pick a solint of 30 seconds, which would allow ~6 solutions over 3 minutes to track the variations.

- Determine the rms for 30 seconds and a bandwidth of 128MHz, a single polarization and 25 antennas in Ka band using the VLA Exposure Calculator.

rmssolint=0.48mJy/beam - Calculate the SNR: SNR=15/0.48=31 (peak/rms, all in mJy/beam)

As this ratio is over 20, this source is good to self-calibrate and therefore one can use the higher APL - Example 2: The science target is a maser line in K band with a line width of ~3km/s (~220kHz). The expected peak flux of the maser is 147mJy over 3km/s or in a ~220 kHz channel and the observation occurs in C-configuration.

- Estimate the solint. The recommended calibration cycle time for C-configuration and K band is 6 minutes so we assume that the atmospheric phases will vary faster than that with the higher APL. So let's pick a solint of 1 minute, which would allow ~6 solutions over 6 minutes to track the variations.

- Determine the rms for 1 minute and a bandwidth of 3km/s or ~220 kHz, a single polarization and 25 antennas in K band using the VLA Exposure Calculator.

rmssolint=10.5mJy/beam - Calculate the SNR: SNR=147/10.5=14 (peak/rms, all in mJy/beam)

This ratio is not near 20 so this maser source is probably not a good source to self-calibrate; use the lower, more restrictive APL.

Caveats

- The theoretical rmssolint might be lower than the actual image rms for many reasons (e.g. RFI, overhead unaccounted for) and therefore self-calibration could be difficult. The SNR ≥ 20 is a slight overestimate of the SNR needed because of the likelihood that the rms will be slightly higher than that given by the VLA Exposure Calculator.

- If the target is dominated by extended emission, the flux detected by longer baselines may be much lower than the peak. It then might be difficult to get good self-calibration solutions on the longer baselines, although uv-restrictions in the self-calibration procedure may help.

- The recommendations and examples above are conservative. There are tricks that can be used to self-calibrate in non-ideal situations. If you are an experienced user and you know you can self-calibrate your science target then please use the higher APL; in that case doing these calculations can be skipped.

Calibration

This section discusses general calibration and calibration strategies when preparing for VLA observations. Specific calibration during post-processing—not depending on data taken during the observations—such as improved antenna positions, opacity and ionospheric corrections, are not discussed here. Note, however, that there is specific guidance with respect to the 8/3-Bit Attenuation and Setup Scans that are required in observing scripts (scheduling blocks).

If you are looking for the listing of VLA calibrators, go to the VLA Calibrator List. This list may also be searched in the Source Catalog Tool (SCT, aka Sources). The OPT manual has a section on how to search in the SCT.

Calibration Basics

What is calibration?

The main goal of calibration is to be able to correct for effects that may interfere with the scientific outcome of a measurement (an observation) due to the instrument and/or local temporary conditions so that these measurements can be compared to other measurements (at other times, other instruments, other frequencies, etc.) and theoretical predictions.

Calibration starts in the device design stage and ends in the final data presentation. Calibration can refer not only to calibration of the data, but also to the instrument as a whole or its separate components. The amount of calibration typically depends on the observing program and the science goal. Some calibrations need to be done once as their solution is fairly constant over time, while other calibrations need to be repeated regularly to capture changing properties over time. For radio astronomy, and in particular interferometry, the following general calibration steps can be identified: calibration of the instrument by observatory staff, calibration of the current observing conditions by the observer, and calibration of scientific results by the data analyzer. Some common calibration examples:

- Calibration of the antenna (receiver frequencies, receiver system temperatures, optics), antenna positions, timing, and correlator visibilities is done by observatory staff.

- Calibration of instrumental delay, instrumental polarization, spectral bandpass response, absolute flux density scale, and other possible properties—assumed to be constant during the observation—should be taken by the observer, typically once or twice during the entire observation for each observed frequency and correlator configuration.

- Calibration of antenna pointing, delay, attenuator and requantizer settings, and other possible properties assumed to be only slowly varying during the observation should be performed by the observer, typically once every hour or so during the observation, or, for example, when switching frequency bands.

- Calibration of antenna gains, atmospheric phase fluctuations, and other possible properties expected to vary more rapidly with observing conditions and geometry during the observation should be performed more frequently than the time scale over which the property changes.

- Calibration of the position of a source with respect to another source, calibration of a frequency to a line-of-sight velocity, calibration of a polarization angle to a reference angle, calibration of the flux density scale of a single source in one observation to another observation of the same source, etc.

The taking of calibration data to be evaluated in the online system or in post-processing happens before, during, and after the observation and also may be applied before, during, and after the observation. Note that most calibration applied before and during the observation, e.g., antenna pointing, take effect during the observation and the calibration must be correct as it cannot be adjusted after acquisition.

It should be understood that calibration is an important part of the observation and must be thoughtfully included in the observation preparation and time request in the proposal. The key point of planning and including calibration is that if the observations are not properly calibrated, the science goal will not be achieved.

When to calibrate?

Calibration should be performed, at the very least, more frequently than the time scale over which the property changes and before that change becomes too large to be compensated for. Nearly constant properties should be calibrated at the start of an observation, when changes from a previous observation by another observer are to be expected. If the constant property can be applied in post-processing, this calibration can also be taken at the end of the observation. Time or geometry dependent changes should be monitored at regular intervals so that the change can unambiguously be interpolated over the observation. Planned, abrupt changes in the observation, such as a frequency change or observing a different part of the sky, would trigger calibration. Last, but not least, a very specific science goal may need a calibration that is not among the standard calibrations described here. The calibration strategy is the responsibility of the observer, but NRAO staff is available for individual advice through the NRAO Helpdesk.

Typical calibration intervals are once during the observation for flux density, bandpass/delay, and polarization angle (per frequency setting and per correlator configuration). It is prudent to at least break up the flux density calibration scan into two or more separate scans, as this is the only calibration for which there is no good alternative if it happens to be corrupted.

Typical intervals for complex gain (amplitude and phase) calibration are dependent on the weather conditions and baseline length. On longer baselines (i.e., on longer uv-distances and therefore more important for high frequency observing), the phase change on the interferometer will be more rapid and requires more frequent calibration than at the lower observing frequencies. An exception at low frequencies is when the Sun affects the ionosphere and rapid changes can be expected near sunset and sunrise. Otherwise, the largest effect on phase change is in the troposphere. The gain calibration uses the assumption that the calibration toward the sky, in which the calibrator source is observed, can be interpolated over time and viewing angle and resembles the same atmospheric conditions toward the sky of the target source. The further away the calibrator from the target, and the longer the intervals of the calibration measurement, the less strict this assumption will hold. It can happen that calibration consumes more than half of the allocated observing time in order to achieve the scientific goal. Fortunately, this may only be necessary at the highest frequencies, in the largest array configurations, and in bad weather conditions. With the introduction of dynamic scheduling at the VLA, this latter variable has been largely eliminated and gain calibration has been easier to plan (see below).

Typical calibration intervals for attenuator settings are at the beginning of an observation. Requantizer gains need to be redetermined after a change of tuning, including when returning to the original observational setup.

Calibration intervals for antenna pointing are largely dependent on the geometry of the observation. As a rule-of-thumb, after tracking for about an hour, the direction of the solutions of the antenna pointing calibration will have changed significantly from where the target position is now—on the order of 20°—warranting a new pointing solution. During the day, because of temperature changes that affect antenna optics, pointing should be repeated roughly every 30 to 40 minutes. Also, when slewing a large distance from the target to a flux density or a bandpass calibrator (over 20° in AZ and/or EL), the antenna pointing will need an updated solution.

How to calibrate?

To ensure that the instrument is delivering the expected measure, the easiest method of calibration is to insert a known signal at the input and analyze the resulting signal at the output. The calibration measurement will yield, after some massaging, the corrections that need to be applied to the output signal to obtain the true representation of the input signal. The uncorrected output signal is also known as the instrumental response for the given input signal. As determining the response directly is not always possible, alternatives may be available. These alternatives require, however, certain trade-offs and choices to be made by the observer depending on the science goals. Observatory staff can advise, and a first attempt is made below. For very specific questions, please ask the NRAO Helpdesk.

A typical calibration signal for the instrumental response of an individual antenna signal path is a pulse (the firing of a noise diode in the receiver) and standard instrumental calibration procedures are available. A typical calibration signal for the total observational response of an interferometer is to observe a point source: a signal that can be considered a simple, single, isolated object with a known constant flux density, polarization as function of frequency, and absolute sky position. As these objects are very rare for high-angular resolution and high-sensitivity interferometers like the VLA, alternatives that dominate the response (not necessarily constant in flux density) and that are near point-like are common trade-offs for any radio interferometer. Many of these calibrator sources are given in the VLA Calibrator List.

Then, depending on the signal property to calibrate, one would choose an adequate calibrator source for the property and insert it at the appropriate place in the observing schedule. This calibration is defined for a certain point in time for certain conditions and needs to be redone when it starts to become invalid. Performing a calibration on the target field—a field where obtaining the measured properties are the goal of the observation—generally is not a good idea. As a reasonable approximation in general, therefore, it is assumed that for the calibration performed near in time and near that field on the sky also holds for the target field and thus can be interpolated over the target observation. NRAO tries to provide guidance for when these assumptions hold for different sets of observations, but the observer should always be aware that certain conditions for successful interpolation of calibration may not apply.

Specific suggestions for different VLA calibrations and how to schedule them are listed elsewhere in the Guide to Observing (High Frequency Strategy, Low Frequency Strategy, and Very Low Frequency Strategy), and the OPT Manual. In this section the focus is on general, non-frequency specific, calibration during the observation by the observer. When making a schedule, consider the hints given here and elsewhere in the documentation. Do not hesitate to contact the NRAO Helpdesk for assistance or further information.

VLA Calibration by the Observer

When seen from the observer's perspective, for any standard observation in each scheduling block, the observer is expected to include calibration of the absolute (flux density) scale, calibration of the signals at different frequencies relative to each other over the observing bandwidth (bandpass), and calibration of the time dependent effects (complex gain (phase and amplitude)) of changing conditions due to the atmosphere and instrument. More sophisticated or challenging experiments may include more specific calibrations as described below.

Flux Density Scale Calibration

The correlator, where signals at specific frequencies from the antennas are combined into visibilities, only processes what it gets fed from the electronics system in terms of relative signal strength and relative phase. The correlator products, therefore, need to be readjusted to represent the flux density as measured from the sky visibilities. At the VLA this means that one observes a calibrator with a postulated (or assumed) known flux density at these frequencies along with the other observations in the scheduling block. In post-processing, the visibilities are then rescaled for this calibrator to the flux density for this frequency. Other visibilities in the same observation, using the same setup, can simply be matched using the relative scale and the absolute flux density of the calibrator.

The flux density scale adopted for the VLA between 1 and 50 GHz is based on the Perley and Butler (2017) standard. This is very close to the traditional Baars et al. scale (1977 A&A 61, 99) between 1 and 15 GHz and includes the Scaife and Heald scale (2012, MNRAS 423, L30) for frequencies below 1 GHz. Distributed versions of AIPS and CASA apply the most recent scale in their SETJY tasks.

Because of source variability, it is impossible to compile an accurate and up to date listing of flux densities for all the VLA calibrators. The values given in the VLA Calibrator List, therefore, are only approximate and for the epoch they were measured. We strongly recommend, and some science objectives require, bootstrapping the flux density of a calibrator by comparing the calibrator observations with one or several observations of 3C286, 3C48, 3C147, or 3C138**. Only in compact configurations and at low frequencies, i.e., typically at L- and P-band in C and D configuration, 3C295 or 3C196 may also be used. However, CASA does not have a flux density scale model for 3C295 or 3C196.

Both AIPS and CASA use model images for the standard flux density calibration sources (see their respective SETJY documentation) to account for their structures which are frequency and array configuration dependent. Alternatively, u,v restrictions, or limitations on the number of antennas, can be used. When using models, the bootstrap accuracy should be within a couple to a few percent. However, at frequencies of about 15 GHz and above, there are appreciable changes in the antenna gains and atmospheric opacity as a function of elevation. By calibrating the target source with a nearby calibrator, much of these variations can be removed. If the flux density scale calibrator (e.g., 3C286) is observed at a different elevation from the complex gain calibrator, however, then the flux density bootstrapping will have a considerable systematic error. For the higher frequencies, a typical discrepancy in actual versus measured flux density scale of the order of 20-30% is not unlikely.

Accurate models are available in both AIPS and CASA for various frequency bands for the calibrators 3C286, 3C48, 3C147, and 3C138**. However, neither 3C295 nor 3C196 has such models and the VLA CASA calibration pipeline will fail if these two calibrators are used. Also, the bright source 3C84 (J0319+4130, not to be confused with 3C48) cannot be used as an absolute flux density calibrator as it is variable, but it serves well for bandpass and delay calibration.

See also the flux density scale discussion in the VLA Observational Status Summary (OSS).

** The flux density scale calibrator 3C138 is currently undergoing a flare. As of January 2025, the change in flux density is greater than 10% at all frequencies greater than 4 GHz (i.e., C-band). At present, the magnitude of the flare is approximately a factor of 2 at K-band, 3 at Ka-band, and 4 at Q-band. Monthly monitoring observations are available for investigators that require an accurate flux density scale when using 3C138. These observations are publicly available in the archive under the project code TCAL0009. A table of scaling factors per band per month from February 2021 onward has been provided.

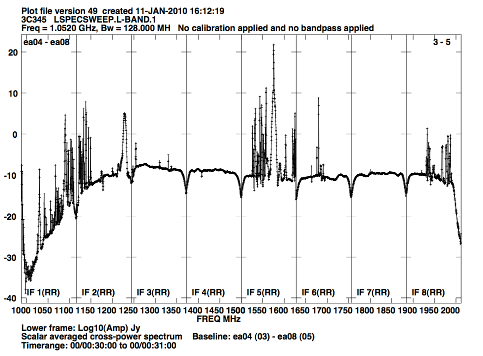

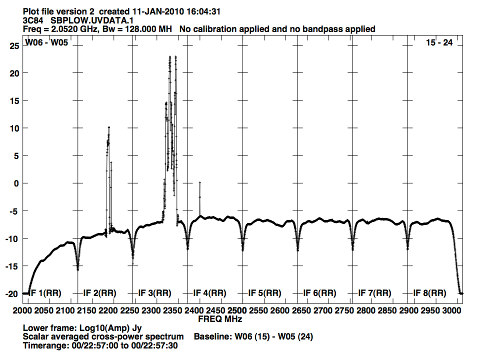

Bandpass and Delay Calibration

Small impurities in the correlator model, such as an inaccurate antenna position, timing, etc., cause small deviations from the model that are noticeable as a time-constant linear phase slope as function of frequency in the correlated data for a single baseline. This phase slope, known as a delay, is a property of the IF baseband and the same for all subbands (spectral windows) in a baseband. If the frequencies in an observation are averaged into a continuum image, an uncorrected delay causes decorrelation of the continuum signal and is not a correct representation of the sky. The delay calibration is determined on a short time interval on a strong source in order to achieve high signal to noise for the solution without including the time dependent variations.

Small impurities in the frequency amplitude and phase response as function of frequency, independent of the delay, also occur and have to be corrected. These corrections are a property of the passband on top of the response of the baseband, and are a property of the subband and the location of the subband in a baseband. Leaving the bandpass uncorrected causes incorrect relative amplitudes and phases and does not deliver the correct spectral representation of the sky. Averaging these uncorrected impurities over frequency into a continuum image limits the achievable signal to noise and dynamic range. As for the delay, bandpass calibration is usually determined on a short time interval on a strong source to achieve high signal to noise for the solution without including the time dependent variations. Delay and bandpass calibration, therefore, is usually performed using the same calibrator. Hereafter in the text, delay calibration is implicitly included in the bandpass calibrator or bandpass calibration scan.