Sensitivity

Sensitivity

The theoretical thermal noise expected for an image using natural weighting of the visibility data is given by:

| \[\Delta I_m = \frac{SEFD}{\eta_{\rm c}\sqrt{n_{\rm pol}N(N-1)t_{\rm int}\Delta\nu}}\] | (eq. 1) |

where:

- - SEFD is the system equivalent flux density (Jy), defined as the flux density of a radio source that doubles the system temperature. Lower values of the SEFD indicate more sensitive performance. For the VLA's 25–meter paraboloids, the SEFD is given by the equation SEFD = 5.62Tsys/ηA, where Tsys is the total system temperature (receiver plus antenna plus sky), and ηA is the antenna aperture efficiency in the given band.

- - ηc is the correlator efficiency (~0.93 with the use of the 8-bit samplers).

- - npol is the number of polarization products included in the image; npol = 2 for images in Stokes I, Q, U, or V, and npol = 1 for images in RCP or LCP.

- - N is the number of antennas.

- - tint is the total on-source integration time in seconds.

- - Δν is the bandwidth in Hz.

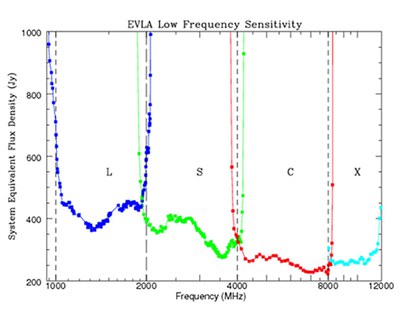

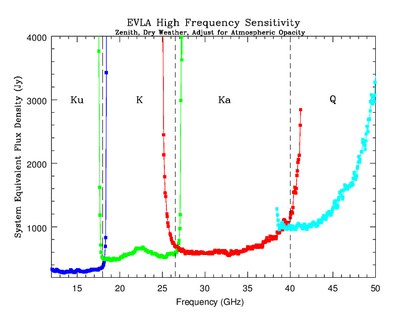

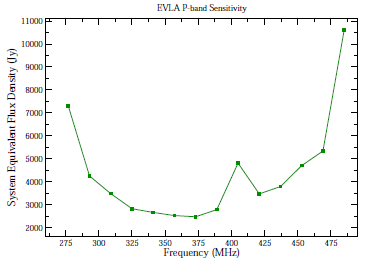

Figure 3.2.1 shows the SEFDs as a function of frequency used in the VLA exposure calculator for those Cassegrain bands currently installed on VLA antennas, and include the contribution to Tsys from atmospheric emission at the zenith. Figure 3.2.2 shows the SEFDs as a function of frequency for the P-band; these measurements are based on imaging of a field far from the galactic plane. Table 3.2.1 gives the SEFD at some fiducial VLA frequencies.

|

|

Figure 3.2.1: SEFD used in the Exposure Calculator for the VLA. Left: The system equivalent flux density as a function of frequency for the L, S, C and X-band receivers. Right: The system equivalent flux density as a function of frequency for the Ku, K, Ka, and Q-band receivers. SEFDs at Ku, K, Ka, and Q bands include contributions from Earth's atmosphere and were determined under good conditions.

Figure 3.2.2: The SEFD used in the VLA Exposure Calculator as a function of frequency for the P-band receiver

Note that the theoretical rms noise calculated using equation 1 is the best limit possible. There are several factors that will tend to increase the noise compared with theoretical:

- For the more commonly used robust weighting scheme, intermediate between pure natural and pure uniform weightings (available in the AIPS task IMAGR and CASA task clean), typical parameters will result in the sensitivity being a factor of about 1.2 worse than the listed values.

- Confusion. There are two types of confusion: (i) that due to confusing sources within the synthesized beam, which affects low resolution observations the most. Table 3.2.1 shows the confusion noise in D configuration assuming robust weighting (see Condon et al. 2012, ApJ, 758), which should be added in quadrature to the thermal noise in estimating expected sensitivities. The confusion limits in C configuration are approximately a factor of 10 less than those in Table 3.2.1; (ii) confusion from the sidelobes of uncleaned sources lying outside the image, often from sources in the sidelobes of the primary beam. This confusion primarily affects low frequency observations.

- Weather. The sky and ground temperature contributions to the total system temperature increase with decreasing elevation. This effect is very strong at high frequencies, but is relatively unimportant at the other bands. The extra noise comes directly from atmospheric emission: primarily from water vapor at K-band, and from water vapor and the broad wings of the strong 60 GHz O2 transitions at Q-band.

- Losses from the 3-bit samplers. The VLA's 3-bit samplers incur an additional 10–15% loss in sensitivity above that expected—i.e., the efficiency factor ηc = 0.78 to 0.83.

| Frequency | SEFD (Jy) |

RMS confusion level |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.39 GHz (P) | 2790 | 5330 | ||

| 1.5 GHz (L) | 420 | 74 | ||

| 3.0 GHz (S) | 370 | 12 | ||

| 6.0 GHz (C) | 310 | 2 | ||

| 10.0 GHz (X) | 250 | negligible | ||

| 15 GHz (Ku) | 320 | negligible | ||

| 20 GHz (K) | 500 | negligible | ||

| 33 GHz (Ka) | 600 | negligible | ||

| 45 GHz (Q) | 1300 | negligible |

In general, the zenith atmospheric opacity to microwave radiation is very low: typically less than 0.01 at L, C, and X-bands; 0.05 to 0.2 at K-band; and 0.05 to 0.1 at the lower half of Q-band, rising to 0.3 by 49 GHz. The opacity at K-band displays strong variations with time of day and season, primarily due to the 22 GHz water vapor line. Observing conditions are best at night and in the winter. Q-band opacity, dominated by atmospheric O2, is considerably less variable.

Observers should remember that clouds, especially clouds with large water droplets (thunderstorms), can add appreciable noise to the system temperature. Significant increases in system temperature can, in the worst conditions, be seen at frequencies as low as 5 GHz.

Tipping scans—which are currently unavailable but will be implemented at some time in the future—can be used for deriving the zenith opacity during an observation. In general, tipping scans should only be needed if the calibrator used to set the flux density scale is observed at a significantly different elevation than the range of elevations over which the complex gain calibrator (amplitude and phase) and target source are observed.

When the flux density calibrator observations are within the elevation range spanned by the science observing, elevation dependent effects (including both atmospheric opacity and antenna gain dependencies) can be accounted for by fitting an elevation-dependent gain term. See the following items:

- Antenna elevation-dependent gains. The antenna figure degrades at low elevations, leading to diminished forward gain at the shorter wavelengths. The gain-elevation effect is negligible at frequencies below 8 GHz. The antenna gains can be determined by direct measurement of the relative system gain using the AIPS task ELINT on data from a strong calibrator which has been observed over a wide range of elevation. If this is not possible, care should be taken to observe a primary flux calibrator at the same elevation as the target.

Both CASA and AIPS allow the application of elevation-dependent gains and an estimated opacity generated from ground-based weather through the CASA tasks gencal and plotweather, and AIPS task INDXR.

- Pointing. The SEFD quoted above assumes good pointing. Under calm, nighttime conditions, the antenna blind pointing is about 10 arcsec rms. The pointing accuracy in daytime can be much worse—occasionally exceeding 1 arcminte due to the effects of solar heating of the antenna structures. Moderate winds have a very strong effect on both pointing and antenna figure. The maximum wind speed recommended for high frequency observing is 11 mph (5 m/s). Wind speeds near the stow limit 45 mph (20 m/s) will have a similar negative effect at 8 and 15 GHz.

To achieve increased pointing accuracy, referenced pointing is recommended where a nearby calibrator is observed in interferometric pointing mode every hour or so. The local pointing corrections measured can then be applied to subsequent target observations. This reduces rms pointing errors to as little as 2–3 arcseconds (but more typically 5–7 arcseconds) if the reference source is within about 15 degrees in azimuth and elevation of the target source and the source elevation is less than 70 degrees. At source elevations greater than 80 degrees (zenith angle < 10 degrees), source tracking becomes difficult; it is recommended to avoid such source elevations during the observation preparation setup.

Use of referenced pointing is highly recommended for all Ku, K, Ka, and Q-band observations, and for lower frequency observations of objects whose total extent is a significant fraction of the antenna primary beam. It is usually recommended that the referenced pointing measurement be made at 8 GHz (X-band), regardless of what band your target observing is at, since X-band is the most sensitive and the closest calibrator is likely to be weak. Proximity of the reference calibrator to the target source is of paramount importance; ideally the pointing sources should precede the target by 20 or 30 minutes in Right Ascension (RA). The calibrator should have at least 0.3 Jy flux density at X-band and be unresolved on all baselines to ensure an accurate solution.

To aid VLA proposers there is an online guide to the exposure calculator; the exposure calculator provides a graphical user interface to these equations.

Special caveats apply for P-band (230–470 MHz) observing. The SEFD's in Figure 3.2.2 or that listed in table 3.1.2 are from an observation taken far from the Galactic plane, where the sky brightness is about 30K. At P-band, Galactic synchrotron emission is very bright in directions near the Galactic plane. The system temperature increase due to Galactic emission will degrade sensitivity by factors of two to three for observations in the plane, and by a factor of five or more at or near the Galactic center. Additionally, the antenna efficiency (currently about 0.31 for 300 MHz) will decline with both increasing and decreasing frequencies from the center of P-band.

The beam-averaged brightness temperature measured by a given array depends on the synthesized beam, and is related to the flux density per beam by:

| \[T_{\rm b} = \frac{S \lambda^2}{2k\Omega} = F \cdot S\] | (eq. 2) |

where Tb is the brightness temperature (Kelvins) and Ω is the beam solid angle. For natural weighting (where the angular size of the approximately Gaussian beam is ∼1.5λ/Bmax), and S in mJy per beam, the parameter F depends on the synthesized beam, therefore on the array configuration, and has the approximate value of F = 190, 18, 1.7, 0.16 for A, B, C, and D configurations, respectively. The brightness temperature sensitivity can be obtained by substituting the rms noise, ΔIm, for S. Note that Equation 2 is a beam-averaged surface brightness; if a source size can be measured, then the source size and integrated flux density should be used in Equation 2 and the appropriate value of F calculated. In general, the surface brightness sensitivity is also a function of the source structure and how much emission may be filtered out due to the sampling of the interferometer. A more detailed description of the relation between flux density and surface brightness is given in Chapter 6 of Reference 1, listed in Documentation.

For observers interested in HI in galaxies, a number of interest is the sensitivity of the observation to the HI mass. This is given by van Gorkom et al. (1986; AJ, 91, 791):

| \[M_{\rm HI} = 2.36 \times 10^5 D^2 \sum S \Delta V ~~~~M_\odot\] | (eq. 3) |

where D is the distance to the galaxy in Mpc, and SΔV is the HI line area in units of Jy km/s.

Connect with NRAO